The personality and history of F L Wright looms over the story of this middle-aged period of his life. Like most geniuses (and that’s how he identified himself) he had unorthodox views on life, unorthodox ways of living, and built unorthodox houses. There had been plenty of drama in his life before the 1920s. In about 1903 he began a none-too-private affair with Marnah, the wife of a client, and in 1909 they went off together on his trip to Europe. He left his wife of twenty year s at home with the six children, and certainly did his reputation great harm.

s at home with the six children, and certainly did his reputation great harm.

On return he built a new base in Wisconsin called Taliesin (tally-ESS-in), a name from his family’s Welsh roots. In 1914, while Wright was away in Chicago, a disturbed employee set fire to the living quarters of Taliesin, and murdered seven people with an axe as they tried to escape, including Marnah and her two children. FLW entered into another marriage in the mid-twenties, which failed within a year, probably due to the wife’s morphine addiction, but then he met Olga and was able to marry her in 1928. This turned out to be a stable and beneficial union.

FLW’s career had had a lean time during the twenties when generally US business was vibrant. It seems that his “organic” approach was not competing well with the stark modernist machined look that had immigrated from Europe. (Ironically, Wright’s own ideas from the Wasmuth Portfolio which he took to Europe in 1909, emphasising arrangements of unadorned rectangular masses, had influenced those later developments.) Then there was the crash of 1929. Wright was 62 and looked like a has-been.

The commission to build Fallingwater ca me at a crucial time for FLW’s career as well as his self esteem, and it all arose indirectly from an initiative put in train by Olga. She was convinced by a Russian guru that the way to live the good life was to be close to the earth and the labour involved in living with it. This was right in tune with FLW’s own outlook and they set up a commune at Taliesin where ‘apprentice’ architects could pay to live close to the master and carry out the labour of breaking rocks, farming, gardening, food preparation and renovating parts of the buildings. Saturday evening was a time for musical concerts.

me at a crucial time for FLW’s career as well as his self esteem, and it all arose indirectly from an initiative put in train by Olga. She was convinced by a Russian guru that the way to live the good life was to be close to the earth and the labour involved in living with it. This was right in tune with FLW’s own outlook and they set up a commune at Taliesin where ‘apprentice’ architects could pay to live close to the master and carry out the labour of breaking rocks, farming, gardening, food preparation and renovating parts of the buildings. Saturday evening was a time for musical concerts.  One of the apprentices was the son of a Pittsburgh department store owner, Edgar Kaufmann, who became interested in FLW’s work. Kaufmann owned a country property an hour and a half from Pittsburgh with holiday cabins for the family and the staff to use. In 1934 he asked FLW to design a house for the family so that they could see the waterfall tumble the thirty meters down the hill. A thorough survey of the site was carried out, partly by some of the apprentices. But Wright neglected this design task for some months, until Kaufmann in frustration rang him at Taliesin to say he was a few hours away and wanted to see the progress on the job. FLW said – “Mr Kaufmann, we’re waiting for you.”

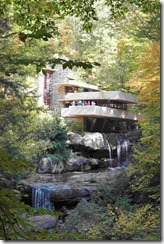

One of the apprentices was the son of a Pittsburgh department store owner, Edgar Kaufmann, who became interested in FLW’s work. Kaufmann owned a country property an hour and a half from Pittsburgh with holiday cabins for the family and the staff to use. In 1934 he asked FLW to design a house for the family so that they could see the waterfall tumble the thirty meters down the hill. A thorough survey of the site was carried out, partly by some of the apprentices. But Wright neglected this design task for some months, until Kaufmann in frustration rang him at Taliesin to say he was a few hours away and wanted to see the progress on the job. FLW said – “Mr Kaufmann, we’re waiting for you.”

Mr Wright (as he was generally called) then sat at the drafting table with a couple of apprentices in train to keep him supplied with sharpened pencils, and proceeded to draw up the plans and elevations for Fallingwater. One of the attendants, Edgar Tafel, reported that “…he knew where every damn tree and every damn boulder was”. The job was finished in just under three hours, when Kaufmann arrived. Of course, Wright decided the house was not set to be looking at the fall but right on top of it, but Kaufmann adjusted to that.

The turmoil, romance and tragedy of the previous twenty-five years of Wright’s life may seem to be a drama of operatic proportions: indeed, there has been an opera written around it – Shining Brow, by Daren Hagen and Paul Muldoon.

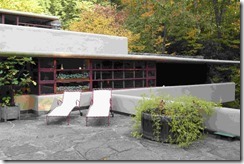

Visual judgments are subjective of course, but for most people the house looks as though it has grown right where it is, surrounded by the trees, but at the same time it has a dynamism that can cause an intake of breath.  FLW’s organic principles are seen in the use of local boulders and quarried rock for the floors and walls, and generally earthy colours in the timber furnishings and the painted window frames. There is a Japanese flavour in the way the windows and doors bring the forest environment in through the glass, and there are often low ceilings. Wright had a lifetime love of Japanese architecture and art since working there in the early twenties. Being on the side of the hill, there was not much scope in the house for large floor space except for the living room, so the cantilevered terraces allow the house to have a feeling of openness, especially useful when a number of guests were visiting.

FLW’s organic principles are seen in the use of local boulders and quarried rock for the floors and walls, and generally earthy colours in the timber furnishings and the painted window frames. There is a Japanese flavour in the way the windows and doors bring the forest environment in through the glass, and there are often low ceilings. Wright had a lifetime love of Japanese architecture and art since working there in the early twenties. Being on the side of the hill, there was not much scope in the house for large floor space except for the living room, so the cantilevered terraces allow the house to have a feeling of openness, especially useful when a number of guests were visiting.

The hanging terraces were a contentious issue during construction, with argument between the engineers, FLW and Kaufmann. It seems that Mr Wright largely had his way, with slight modifications to his engineering, and he was never one to countenance backing down from a decision. In any case, over time the terraces did sag appreciably, and around the year 2000 some major reinforcement was put in place, at a cost of several million dollars.

References

Documentary film, Frank Lloyd Wright, by Ken Burns and Lynn Novick, Florentine Films, 1998

Docent, ‘In-Depth Tour’, Fallingwater, Western Pennsylvania Conservancy

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fallingwater